Feet

8/30/2018

Wing chun is primarily an art learnt from direct transmission. I am very hands on, this comes from thousands of hours wing chun teaching experience and hundreds of hours of training to be a teacher of the Alexander Technique. Most people do not sense their own tension and when you ask them to relax they either cannot do it or they collapse. At first it is really hard to tell the difference between relaxing, pulling down and collapsing, and this is why hands-on teaching is the only reliable first hand way to understand how your body works. The learning method involves touch to encourage muscular release so the mind can trace a connection to the body, then later once the pathways are clearer this can usually be done by verbal reminder. The final outcome is that you establish the connections yourself and importantly how to use them. It is not quick or easy, but what meaningful pursuit is?

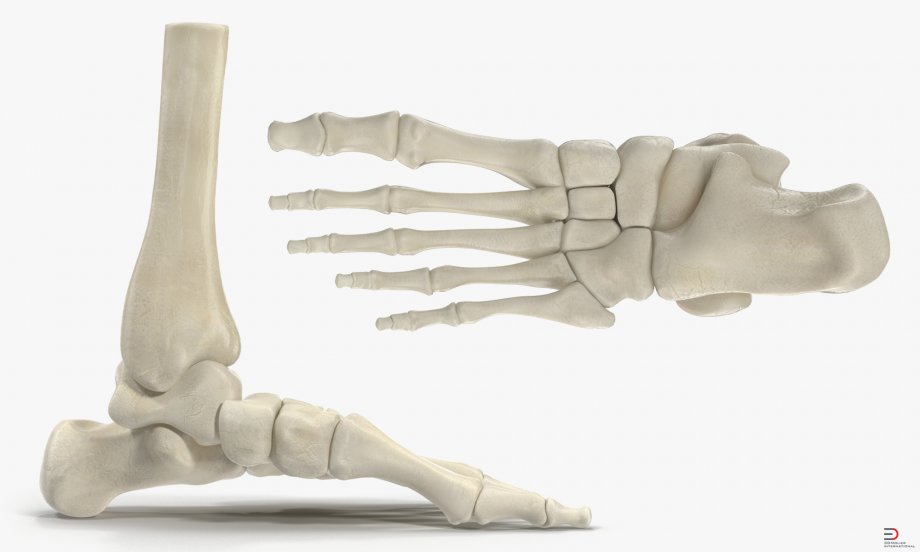

Different areas are easier to relax than others, I tend to work on the shoulder area with new students as most people carry a lot of tension around there, the neck and upper back. Freeing up the shoulder girdle has an immediate effect on how we can handle and produce force. The pelvic area is the most difficult. It is almost always loaded with the weight of the upper body and misaligned due to having to sit or stand all day in awkward positions. It takes time to release deep muscles, this is one of the main reasons that in CST wing chun we advocate standing practice to help the mind get in touch with this areas and dissolve the tension. As a teacher, I do not usually touch peoples feet, but for most they are an area of tension which they are not aware. When force enters our bodies they have to transmit that energy to the floor, so they are a very important link in the chain. You might not think about the tyres of your car much, but get a small puncture and you are not going anywhere. I spent the first several years of my training trying to relax down, relax into the ground (I call this period my pre-Hong Kong training). Without hands on guidance I was relaxing as much as I was collapsing. I now look at my feet and realise that collapse has impacted on my ankles and arches. We do not stand on our feet, we should stand on the ground. The foot is not a flat plimsoll, it is alive; an elaborate vertical construction made of arches. It is not to be pulled down, the earth is coming up towards us. As an experiment think of your naked foot as a hiking boot, the heel separate from the front of the ankle, the back supported and thrust upwards. The balls of the toes take their proportion of the weight and the toes are allowed to lengthen and separate. Allow the hidden support in the arch, be aware of whether your feet collapse in or if you stand on the outer part. If there is only partial contact with the ground the chain of postural muscles within your body will not active and you will have to hold yourself up instead with the wrong muscles (which quickly fatigue). Have a quick look at where your heel is, it is probably further back than where you sense. This is because you probably hold yourself in the front of the ankle. Instead allow the weight to drop into the heel so the support can rise up from the back of your body. Imagine yourself landing on a trampoline and the sensation of release as you are taken up. The irony here is that I do not wear hiking boots, in fact I do not wear shoes with heels. I wear barefoot/minimalist shoes. Although I want the mental idea of an arch, the feeling of support, most shoes restrict the feet and an elevated heel force the body weight to the front which means we have to grip our muscles. We then tend to walk on our feet and lock the ankles and knees. Below is a picture of the foot, remind yourself how long your toes are (they go right into the foot), where you heel is and how delicate an instrument it is. You could think of your foot as a hand and see what changes that makes.

2 Comments

Shapes

8/17/2018

I think most people have got wing chun wrong, in fact traditional martial arts can be so misinterpreted it risks the whole point of them becoming ineffective. If we take fighting strategy out of the equation for a moment, what we have left is body mechanics. If you do not have good body mechanics, your strategies and techniques will never work. Look at successful fighting arts like boxing, BJJ and wrestling, they have good fundamentals, they emphasis physical conditioning, they use there bodies well (good alignment and leverage relative to the opponent) and they stick to basic principles. They may be ‘external’, but they are effective and the fighting strategies of the arts are relatively easy to apply to the mechanics.

I look at wing chun and I see crazy ideas about optimal angles, perfect shapes etc. What? Optimal relative to what exactly, to who? How can you have an arm shape which is fixed using muscles intended to retard your movement and then call that logical. Why is using your lat muscles to pull your arm into the centre of your body effective in dealing with a force directed at you? Force will come at you from multiple angles and will be ever-changing, and so shape is fleeting. Someone I have always admired a lot is Tony Psaila. Like me he is a grand-student of Chu Shong Tin, although he has trained a lot longer than me and has taught at a high level for many years. A line in one of his videos has always stuck in my head ‘it is not the shape of the arm, it is the state of the arm that matters’. Although shapes are talked about a lot even within my lineage, if you look at greats like CST, Tony Psaila or Sifu Ma Kee Fai, they do not keep static shapes, their movement ebb and flow, arms adapting to the pressure relative to the opponent. And this is my point, your arm position has to be relative to what it is doing, relative to where you are in space and where your opponent is. I would go as far as to say ‘it is not the shape of the body, it is the state of the body that is important’, on the basis that you cannot treat your arm as not being part of your body. The biggest mistake I see with people trying to use relaxed body structure within their wing chun is that even when they start to tap into using their body mass, they then return to putting their arms into shapes not relative to the situation at hand. Why do a tan, fook or bong if that involves removing your focus from your opponents centre. As soon as you chase the hand you are aligning in the wrong direction. You undo your good work. Instead of trying to do wing chun, you should work the fundamental training processes and let your body do the wing chun for you. Ultimately we seek a method where are no techniques, no hand positions, just point and made the decision as whether you strike. If a bong or a fook shape appears, so be it. This probably makes little sense to people who have not practiced this way. From experience I know it does not come across in words or even video, you have to feel it and do it before you can intellectualise it. One thing I will say is that you do need to think through some basis fundaments. Namely, how does your body deal with force? You only have two legs so a horizontal force is always going to put pressure on your shoulders, lower back and hips. You can use a ‘rear leg’, but that will start the process of alignment which will be only strong in one direction (unfortunately people will adapt and move when they want to hit you). Everyone into ‘internal arts’ now says ‘use the floor’ or ‘jin path’. This may help you avoid localising force and getting it locked in your joints, but even if you direct it to the ground from the contact point unfortunately the ground will not magically eat it up; it will not seep to the core of the earth. In fact all that ultimately gives you is an anchor point but you will still have to deal with an equal and opposite force existing between the floor and your contact point with the opponent. Even when you punch someone you have to deal with that equal and opposite force. Fine if you have the conditioning of a boxer, but not fine for those who do not train that way. What we are left with is our relationship with gravity, our relationship with the opponent and how we deal with the two. Arm shapes do not really help with this. It comes back to the work we do with standing practice, our relationship with ‘up’ and how you have ‘make’ your opponent carry your weight. That I can only teach with hands on experience. The shapes you eventually make may look like in the wing chun forms, but it is how the joints and the body reacts to force which is more important. A final few questions to anyone still reading. Do you practice CST wing chun and if so is standing practice a core part of your training? Do you really understand why you do it, in the sense of why it will help you deal with force? If you don’t do standing practice, it you do not understand why you do it then my final questions to you are why? Are you sure it is CST wing chun? |

AuthorKeeping you up to date with what is happening in class Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed